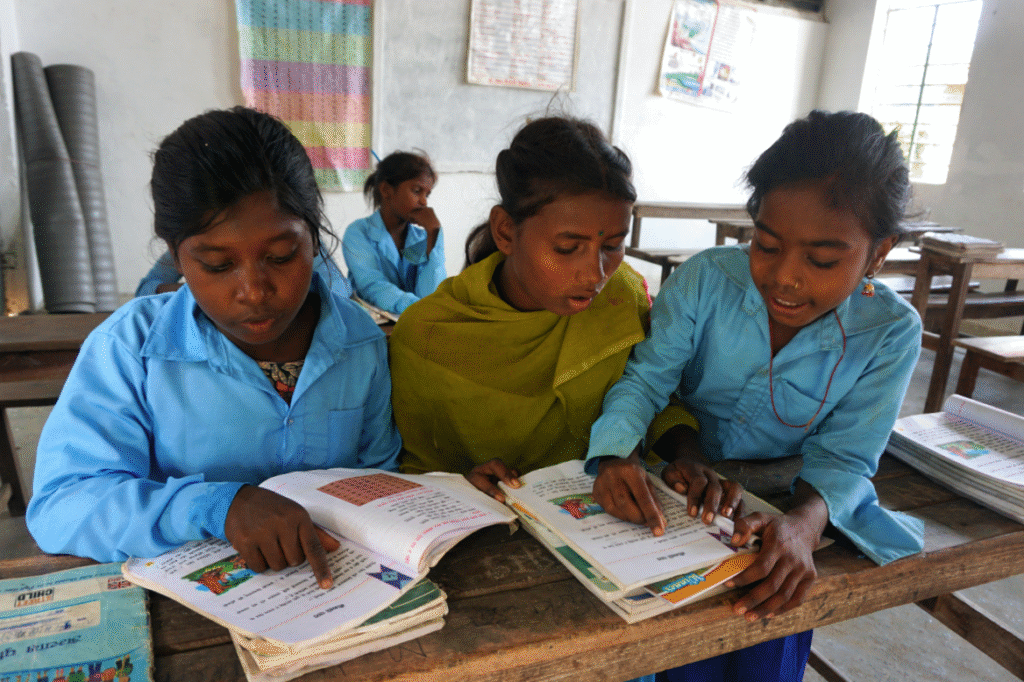

child education with environmental outcomes is no longer speculative: primary education shapes how children understand local ecosystems, influences household practices, and can strengthen community responses to environmental risks. For Comilla — where the Gomti River and urban waste challenges directly affect daily life — the educational sector has an outsized role to play in local sustainability and public health.

How primary education influences environment outcomes

Primary schools teach knowledge, but also habits and social norms. Studies from Bangladesh show that primary students’ environmental literacy (knowledge, attitudes, and participation) varies by urban–rural settings and that classroom-based environmental education increases awareness and willingness to act. When schools include practical, locally-relevant lessons (water safety, sanitation, solid-waste separation), children transfer those behaviors to families — for example, persuading households to use safer water sources or to separate waste.

Evidence from Bangladesh and relevance to Comilla

National education data confirm strong primary enrollment and broad reach of primary institutions — a major advantage for scaling environmental education across households. Bangladesh’s Directorate of Primary Education (APSS/APSC) reports high coverage, making the primary system a feasible channel for climate and environmental interventions. At the same time, local studies of the Gomti River document pollution and seasonal water-quality changes that produce immediate health and livelihood risks for Comilla residents — problems that school-based environmental programs can address through hygiene, pollution awareness, and community mobilization.

Pathways of impact — from classroom to community

- Behavior change: Curriculum modules and school activities (e.g., child-led water testing, waste audits) have successfully shifted family practices elsewhere in Bangladesh (e.g., arsenic mitigation programs delivered through schools). Children often act as credible messengers within households.

- Early-warning and resilience: Teaching children to recognize environmental risks (flood signals, polluted water) increases community preparedness and reduces vulnerability during climate extremes. Recent global reporting also shows school closures and learning loss from heatwaves — a reminder that education and climate adaptation are mutually dependent.

- Citizen science & monitoring: Primary students can participate in simple monitoring (river cleanliness checks, plastic counts), generating local data that civic groups and Comilla City authorities can use to prioritize interventions. Local SFD and city sanitation diagnostics already show clear gaps where community-gathered data would help.

Recommendations

- Integrate local case studies into the curriculum: Use Gomti River pollution data and local waste maps so lessons feel immediate and actionable.

- Adopt experiential learning: School gardens, river-clean days, and water-testing clubs convert knowledge into behavior.

- Partner with local NGOs and City Corporation: Leverage existing SFD and water-quality reports to design projects that produce usable data and visible outcomes.

- Monitor outcomes: Use simple indicators (household use of safe water, incidence of open dumping near homes, student environmental knowledge) tied to school activities so success is measurable and publishable for academic audiences.

Significance and gaps

Although Bangladesh has multiple recent studies on environmental literacy among primary students and documented cases of school-led household change, there remain gaps in longitudinal evidence linking primary education interventions to measurable local environmental outcomes (water quality, waste flows, ecosystem health) in specific cities like Comilla. Filling this gap would require mixed-methods community trials and school–community participatory monitoring.

“We need longitudinal, city-level research to prove what practice-based school programs can achieve for river health and urban sanitation in Comilla.”

Conclusion

Child education at the primary level is a promising, scalable lever for improving environmental outcomes in Comilla. With targeted curriculum content, experiential programs, and partnerships between schools, NGOs, and the City Corporation, primary education can convert widespread classroom reach into cleaner water, safer sanitation, and stronger local climate resilience.

References

Awal, S. T., & Haque, K. I. (2024). Environmental literacy among primary level students in Bangladesh: A comparative study between urban and rural areas. Teacher’s World: Journal of Education and Research.

Directorate of Primary Education (DPE). (2025). Annual Primary School Statistics (APSS) 2024 (Main Report). https://dpe.portal.gov.bd. Department of Primary Education

Directorate of Primary Education (DPE). (2023). Annual Primary School Census (APSC) 2023. https://dpe.gov.bd. Department of Primary Education

Joseph, G., et al. (2023). Early-life exposure to unimproved sanitation and delayed ... ScienceDirect (study on exposure and child outcomes).

NIH / FIC. (2016). School program in rural Bangladesh reduces arsenic exposure. GlobalHealthMatters. (Example of school-led household behavior change).

Yasmin, F., et al. (2023). Evaluation of seasonal changes in physicochemical and ... (Gomti River water quality study).

Cumilla City sanitation diagnostics (SFD Lite) report. (Year). SFD Lite Report: Cumilla City Corporation.

UNICEF. (2024). Youth perspectives on climate change and education in Bangladesh. UNICEF Knowledge.