Introduction

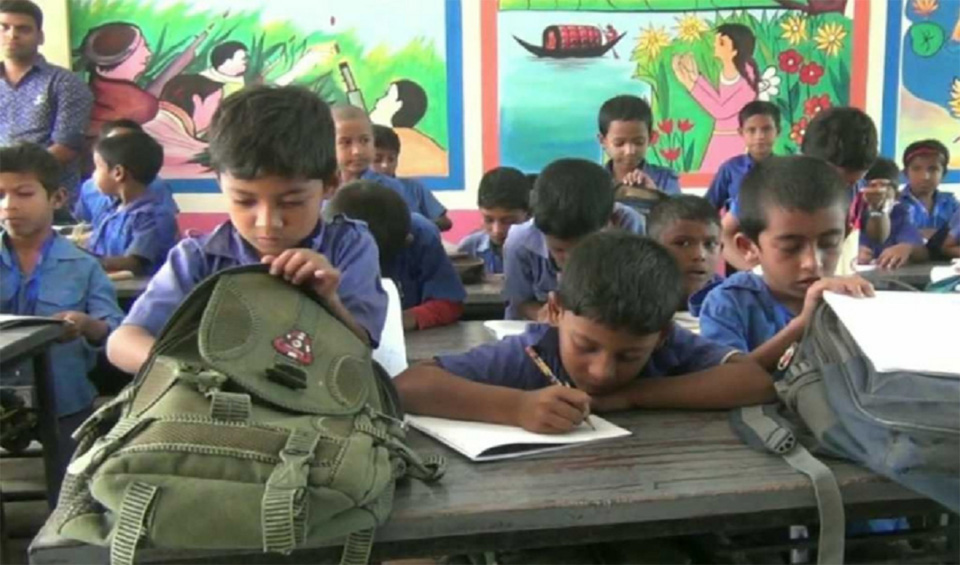

Bangladesh faces significant challenges in providing quality education to its most vulnerable children, particularly orphans and street-connected youth. With more than 49,000 children estimated to be in residential care facilities, the country's education landscape for orphaned children operates through a fragmented system involving government institutions, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and faith-based madrasahs. Understanding the comparative effectiveness of these different institutional approaches is crucial for improving educational outcomes and life prospects for disadvantaged children.

Historical Context and Policy Framework

Following independence in 1971, Bangladesh's constitution recognized education as a fundamental right. Article 17 mandated the state to establish "a uniform, mass oriented and universal system of education" and extend "free and compulsory education to all children" (Bangladesh Constitution, 1972). However, implementation has been challenging, particularly for marginalized populations including orphans and street-connected children.

The mid-1980s marked a turning point, particularly after the Jomtien conference, when both government and NGO sectors launched new initiatives to promote primary education. These included free and compulsory primary education, scholarships for girls, food-for-education programs, and the proliferation of non-formal education programs by NGOs. Despite these efforts, Bangladesh continues to struggle with educational access and quality, especially in rural and underserved urban areas.

There is neither a uniform childcare policy nor formal aftercare support provision in Bangladesh; instead, the government, NGOs, and madrasahs all have their own approaches and methods, creating a complex and often inconsistent landscape of care and education for orphaned children.

Types of Residential Care and Educational Institutions

Bangladesh's residential childcare system operates through five distinct categories:

- NGO-Run Homes: Private non-profit organizations focusing on development and poverty alleviation

- Government Institutions: State-operated facilities with standardized policies

- Faith-Based Community Centers: Religious organizations, particularly madrasahs

- Local Elite-Run Facilities: Community-based initiatives by wealthy individuals

- Armed Forces-Operated Centers: Military-affiliated care institutions

Each type operates with different philosophies, resources, teaching methodologies, and outcome measures, creating significant variation in educational quality and life outcomes for children.

NGO Education Programs: Strengths and Innovations

Research from Mohanpur Upazila in Rajshahi District reveals impressive performance metrics for NGO-operated primary schools. Among surveyed respondents, 97.6% rated classroom observation as "good" in terms of educational development, while 92.7% rated teaching methods favorably. Guardian satisfaction was equally high, with 97.6% viewing NGO schools positively in the Bangladesh context.

Teaching Methodology and Flexibility

NGO schools have demonstrated several innovations:

- Flexible Hours: Accommodating children who must work to support themselves or families

- Student-Centered Approaches: Active learning methodologies rather than rote memorization

- Smaller Class Sizes: Better teacher-student ratios enabling personalized attention

- Community Participation: 85.4% of guardians believed NGO programs should be expanded

NGO models such as BRAC, GSS (Gonoshahajjo Sangstha), CMES, NIJERA Shikhi, UCEF, and DUSHTHA SHASTHYA Kendra have developed distinctive non-formal primary education approaches tailored to disadvantaged children's needs. These models emphasize practical life skills alongside academic content and maintain strong community linkages.

Teacher Quality and Completion Rates

A significant finding shows that 92.3% of NGO school teachers complete their courses within the designated timeframe, suggesting better training systems and institutional support compared to some government facilities. However, NGO teachers often face lower salaries and less job security than government counterparts, potentially affecting long-term retention.

Government Education Programs: Challenges and Resources

Government-operated orphanages and primary schools benefit from established infrastructure and standardized curricula. Following independence, the government introduced universal primary education and created eleven types of primary schools ranging from formal to non-formal and secular to religious-oriented institutions.

Structural Advantages

- Formal Recognition: Government certificates carry official weight for further education

- Resource Allocation: Access to state budgets and international donor funding

- Teacher Training: Formal teacher preparation programs and continuing education

- Infrastructure: Permanent buildings and facilities in most areas

Persistent Challenges

Despite constitutional mandates and policy initiatives, government primary education faces significant obstacles:

- Dropout Rates: Children increasingly leave school before completing primary education

- Access Barriers: Many upazilas cannot fulfill enrollment targets, particularly in remote areas

- Poverty-Related Non-Enrollment: Family economic pressures prevent school attendance

- Quality Issues: Expansion in quantity has not been matched by quality improvements

- Teacher Absenteeism: Lower attendance rates compared to NGO schools

Research indicates that while government schools have broader coverage, they often struggle with classroom management, teacher motivation, and student engagement—areas where NGO schools frequently excel.

Comparative Outcomes: Children's Lived Experiences

A qualitative study of 33 young people aged 12-26 who had experienced residential care in Bangladesh revealed nuanced findings about institutional effectiveness. The research compared experiences across NGO-run, government-operated, and madrasah institutions through in-depth interviews and observational methods.

Positive Impacts

Most participants reported benefiting from institutional care, with care experiences having largely positive impacts on their lives. Success factors included:

- Attachment to Trusted Adults: Those who developed relationships with mentors showed better outcomes

- Peer Support Networks: Strong friendships provided emotional resilience

- Educational Access: Opportunities unavailable in their families of origin

- Basic Needs Met: Food, shelter, and safety providing stability

Negative Experiences and Disparities

However, experiences varied significantly based on institution type. Children who were evicted or aged out without proper support "suffered a range of hardships after leaving care." Key findings included:

- Societal Discrimination: Despite developing resilience, young people faced prejudice limiting opportunities

- Inadequate Aftercare: Support varied by institution and was generally informal

- Cultural and Systemic Factors: Institution culture, systems, and practices significantly affected outcomes

The research demonstrated "a connection between the in-care experience and the success of a young person in the outside world," with institution type, care quality, and socio-cultural-religious influences all playing crucial roles.

COVID-19 Impact: Revealing Systemic Vulnerabilities

The outbreak of COVID-19 exacerbated the plight of street-connected children, exposing critical weaknesses in both government and NGO support systems. Government administrative actions taken through lockdowns and restrictions disrupted the lives and livelihood of street-connected children.

Research from Dhaka revealed that pandemic conditions caused job losses, restricted earning opportunities, and intensified suffering from hunger, homelessness, and abuse. Children were deprived of education, healthcare, and social services. While child welfare service providers came forward to serve the children with food aid and emergency services in collaboration with a few community-based voluntary organizations, the services were not enough to address children's needs and problems.

This crisis highlighted that NGOs, despite their flexibility and community connections, lacked resources for sustained emergency response, while government systems proved too rigid to adapt quickly to changing needs.

Recommendations for Improvement

Based on comparative analysis, several recommendations emerge:

For Policy Makers

- Develop Unified Childcare Policy: Create comprehensive guidelines applicable across all institution types

- Establish Formal Aftercare Systems: Structured support for young people transitioning from institutional care

- Standardize Quality Benchmarks: While allowing flexibility in methods, ensure minimum standards

- Increase Resource Allocation: Particularly for NGO teacher salaries and infrastructure

For Practitioners

- Community Engagement Strategies: Multi-stakeholder collaboration for comprehensive support

- Mentorship Programs: Facilitate attachment between children and trusted adults

- Emergency Preparedness: Develop contingency plans for crises like pandemics

- Cultural Sensitivity: Incorporate faith and religious beliefs appropriately in upbringing

For Research

Further mixed-methods research should examine child maltreatment, long-term outcomes by institution type, and cost-effectiveness of different models.

Conclusion

The comparative study of government versus NGO-run orphan education programs in Bangladesh reveals that neither system is uniformly superior. NGO programs demonstrate advantages in teaching methodology, flexibility, community engagement, and guardian satisfaction, with 84.6% showing positive contributions to educational development. However, they face resource constraints and sustainability challenges.

Government programs offer formal recognition, broader infrastructure, and standardized curricula but struggle with quality, teacher motivation, and dropout rates. The most successful outcomes emerge when children develop strong relationships with caring adults, maintain peer connections, and receive community support—factors that transcend institutional type.

The research suggests that "improving financial resources may not necessarily lead to better outcomes from children and young people. Instead, building relationships with adults, peer groups, parents, and community offer the best chance for good outcomes." This insight challenges conventional development approaches and highlights the importance of socio-emotional factors alongside material resources.

As Bangladesh continues developing its childcare and education systems, the path forward requires integration of NGO innovations with government resources and reach, unified by comprehensive policy frameworks that prioritize children's holistic development and long-term success.

References

Bangladesh Constitution. (1972). Article 17: Education.

Biehal, N., Clayden, J., Stein, M., & Wade, J. (1995). Moving on: Young people and leaving care schemes. HMSO.

Mendes, P., & Moslehuddin, B. (2004). Graduating from the child welfare system: A comparison of the UK and Australian leaving care debates. International Journal of Social Welfare, 13(4), 332-339.

Stein, M. (2002). Leaving care: Young people's transitions from care to adulthood. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Suha, S. M., Alam, M. F., Shah, S., Sarkar, S., & Roza, M. A. (2023). COVID-19 risks and vulnerabilities of street-connected children: A qualitative study in Bangladesh. Journal of Social Service Research, 138-156. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2023.2277305

UNICEF. (2008). Children in residential care in Bangladesh. United Nations Children's Fund.

Wickenden, M., & Kuchah, K. (Eds.). (2017). Education in South Asia and the Indian Ocean Islands. Bloomsbury Publishing.