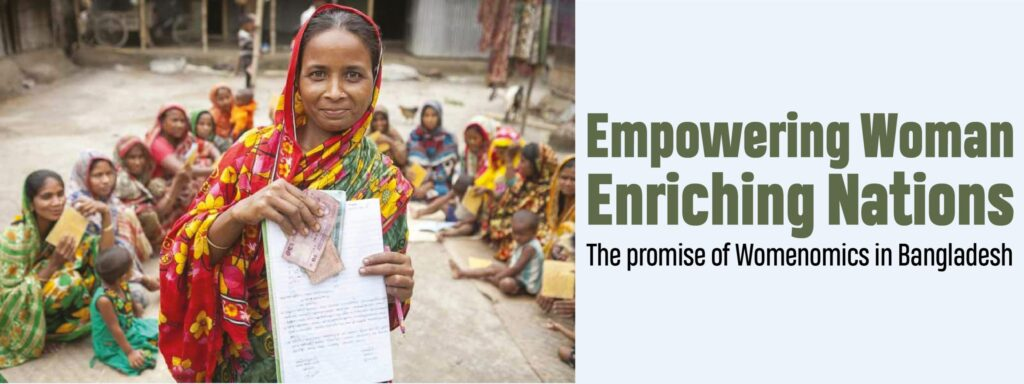

Picture Credit: BBF

The reality of women's empowerment in Bangladesh—particularly in areas like Cumilla—remains scattered and limited despite decades of investment, awareness campaigns, and focused development projects. With a particular emphasis on Cumilla, this article explores the development of women's empowerment programmes in Bangladesh. The paper makes the case that, despite some advancements in labour force participation and education, structural patriarchy, instrumental donor logic, and fragmented governance still threaten long-term sustainable empowerment. It bases this claim on national data, scholarly literature, and policy reviews. It ends with suggestions for inclusive, transformative, and locally based tactics.

As Bangladesh celebrates over five decades of independence, the conversation around women’s empowerment has taken centre stage in development discourse. Cited as one of the country’s most notable social advancements, improvements in literacy, health access, and labour force participation are often praised. According to World Bank data (2023), female labor force participation rose from 23% in 2000 to approximately 36% by 2020. However, statistics often conceal the deep-rooted inequalities and cultural barriers that persist—especially in rural areas like Cumilla.

This article critically evaluates why women’s empowerment initiatives in Cumilla have often failed to yield transformative change, despite the proliferation of NGOs, donor-funded projects, and policy frameworks.

Background: Framing Empowerment in Bangladesh

In the 1970s and 1980s, women’s empowerment in Bangladesh was largely framed through a donor-driven, instrumentalist lens, emphasising women’s roles in poverty reduction and economic productivity rather than their rights (Nazneen & Sultan, 2009). The proliferation of microcredit schemes, literacy campaigns, and reproductive health programs sought to empower women but often failed to address structural patriarchy.

By the 2000s, empowerment began to be understood in broader terms, including decision-making power, mobility, access to justice, and political voice. Yet, the concept of power remains contested across development actors, with donors, political parties, and women’s organisations all framing empowerment differently (Hossain, 2017).

Methodology and Data

This article draws on:

- Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS 2007, 2017)

- Analysis of EDMI (Economic Decision-Making Index) and HDMI (Household Decision-Making Index)

- Case studies, including Cumilla-specific field data from Save Earth Society and BRAC

- Feminist literature and development critiques

The Limits of Empowerment in Cumilla

Economic vs. Household Decision-Making Gaps

Data from BDHS 2007 shows that women in Cumilla and similar rural districts have higher EDMI than HDMI scores, indicating that while women may participate in economic decisions (e.g., buying groceries, budgeting), they remain marginalised in household governance, particularly in decisions around healthcare, marriage, or education for their children (Kabeer, 2011).

“Women in our village earn from tailoring but still need their husband's permission to spend the money,” reports a fieldworker from Save Earth Society in Debidwar, Cumilla.

Urban–Rural Divide

Urban women show significantly higher empowerment indices compared to rural women. The mean EDMI in urban Cumilla is 0.697, while HDMI lags behind at 0.646. This urban-rural disparity reflects not just infrastructure gaps but cultural differences in gender norms and exposure to public life (BBS & UNICEF, 2019).

Token Participation in Governance

Although the Bangladesh government has introduced quotas for women in Union Parishads, findings from governance studies show that most elected women serve as proxies for their husbands or male relatives (Nazneen & Tasneem, 2010). In Cumilla, field research by Save Earth Society shows that less than 20% of female union members attended all official meetings independently.

Why the Initiatives Fail: Core Challenges

Instrumentalist Approaches

Many empowerment programmes are designed not for rights-based transformation but to serve donor goals such as increasing GDP, improving health indicators, or enhancing project outputs (Hossain, 2017). As a result, empowerment is measured by outputs rather than outcomes—such as how many women received training vs. how many became leaders.

Disconnect Between Local Needs and National Policy

National initiatives often fail to engage local women in Cumilla in the design or evaluation of empowerment projects. A study of 569 unions showed that top-down governance mechanisms result in women’s continued exclusion from meaningful public participation (Akhter & Rahman, 2021).

Patriarchal Gatekeeping

In households across Cumilla, male authority remains the norm. Girls are still expected to marry early, restrict mobility, and prioritise family duties. Without challenging these norms, even the best-intentioned programmes collapse under social pressure.

Under-representation in Decision-Making Structures

Despite constitutional guarantees, women remain under-represented in political, legal, and institutional systems. They rarely lead unions, NGOs, or cooperatives. Even within women-led organisations, senior positions often go to elite, urban women, marginalising rural voices.

Case Study: Cumilla's NGO Landscape

Cumilla is home to active NGOs like BRAC, Save Earth Society, and Sajida Foundation, all of which run programmes on gender, microcredit, and education. Yet even within these:

- Projects are often short-term and dependent on donor cycles

- Limited monitoring to ensure follow-through after initial support

- Programs emphasize “empowerment training” without enabling structural shifts like land access, childcare, or legal aid

“After the training ended, no one came back,” said a woman from Sadar Dakshin, Cumilla. “We had no machine, no capital, and no buyers for our products.”

Lessons from the Field

Despite these challenges, many rural women in Cumilla show remarkable agency in subtle ways:

- Forming savings groups to avoid debt traps

- Secretly funding daughters' education against family pressure

- Running informal schools or awareness circles in their communities

These micro-resistances are often overlooked in formal empowerment metrics, yet they are the true roots of change.

Recommendations

Rethink Metrics

Go beyond HDI and EDMI to measure emotional, legal, and relational autonomy. Include metrics like:

- Ability to refuse marriage

- Decision-making on sexual health

- Access to justice and police protection

Foster Community-Led Programs

Empowerment must emerge from within communities. Support women’s cooperatives, peer-led training, and local media by and for rural women.

Invest in Structural Change

Address land rights, education quality, access to transport, and women’s legal representation.

Hold Donors Accountable

Ensure long-term funding, local ownership, and impact-driven evaluations, not just numeric success.

Women’s empowerment in Cumilla

Women’s empowerment in Cumilla—like much of rural Bangladesh—remains uneven, instrumental, and often symbolic. While NGOs, donors, and governments have helped open doors, the path ahead requires deeper, messier work: challenging patriarchy, redistributing power, and listening to rural women themselves.

If we are to truly empower half the population, we must stop treating them as beneficiaries—and start recognising them as leaders of their own liberation.

References

Akhter, S., & Rahman, M. (2021). Gender, Governance and Good Practices: A Local Government Perspective in Bangladesh. Journal of Public Administration and Policy Research, 13(3), 36–45.

Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) & UNICEF. (2019). Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019: Final Report.

Hossain, N. (2017). The Aid Lab: Understanding Bangladesh’s Unexpected Success. Oxford University Press.

Kabeer, N. (2011). Between Affiliation and Autonomy: Navigating Pathways of Women’s Empowerment and Gender Justice in Rural Bangladesh. Development and Change, 42(2), 499–528.

Nazneen, S., & Sultan, M. (2009). Structures of Patriarchy: The Political Trap in Women’s Empowerment Programs. IDS Bulletin, 41(2), 36–42.

Nazneen, S., & Tasneem, S. (2010). A Silver Lining: Women in Reserved Seats in Local Government in Bangladesh. IDS Bulletin, 41(5), 35–42.

Save Earth Society. (2023). Field Observation Report on Women's Empowerment in Cumilla. Unpublished.

World Bank. (2023). Bangladesh Female Labour Force Participation Rate 1990–2022. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org